Christianity, Patriotism, and America – Part 2

Editor's Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Regent University, its faculty, administration, or affiliates.

In Part 1 of this series, I argued that Christians should aspire to the virtue of patriotism. I also defined patriotism as love of one’s homeland. It is fitting that as we approach the 250th anniversary of the United States of America that we also consider what patriotism means in our American context.

To do so, we must depart from a strict adherence to the literal meaning of the word, for American patriotism has always meant something more than mere love of place. The words of two of our greatest Presidents – Washington and Lincoln – show that American patriotism means dedication to the American constitutional order. And that means that our political allegiance must be primarily neither to “blood and soil” nor to a particular politician.

Washington’s Republican Patriotism

At America’s first presidential inauguration in 1789, George Washington wore neither purple ermine nor crown. Instead, his attire was a plain brown shirt. Its simple elegance signified two things. First, Washington wished to be seen as one of the people, for that is what he was. There were to be no kings in America. Second, he sought to direct the eyes and hearts of Americans away from himself and toward the new constitutional and republican order. (For more on this theme, see Stephen Knott’s The Lost Soul of the American Presidency.)

This lesson he taught by symbol at the inauguration he explained by precept in his 1796 Farewell Address, in which he urged that Americans think of themselves as Americans: the Union and the name “American” should always evoke more patriotism, he said, “than any appellation derived from local discriminations.” For Washington as for the other Founders, patriotism meant loyalty not to blood or merely to soil but to constitutional order and to the principles that it represented and protected. For this reason, he called for Americans to “resist with care the spirit of innovation” upon the principles of the Constitution, though some proposed innovations may have a deceptive appearance of wisdom.

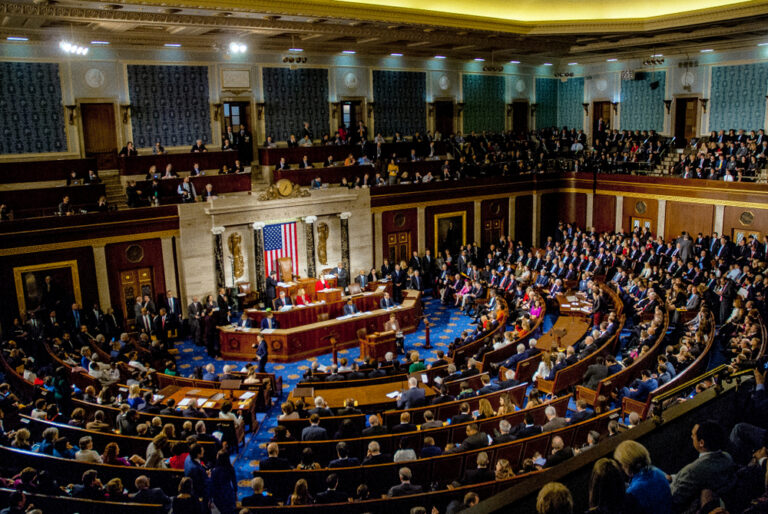

Americans must, he said, be particularly on guard against “cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men” who attempt to “subvert the Power of the People, and to usurp for themselves the reins of government.”

While Americans should reverence their Constitution, the real point was not the law itself or the name “American.” The point was that Americans should be attached to their constitutional order because “Liberty…will find in such a Government” as that erected by the U.S. Constitution “its surest Guardian.” Therefore, Americans should patriotically regard the Constitution as being “sacredly obligatory upon all.”

Lincoln’s Republican Patriotism

Like Washington, Lincoln believed that patriotism consisted in loyalty and affection for the American constitutional order, for it is in this order that Americans find security for political liberty and for political equality. In his 1838 Lyceum Address, Lincoln warned that for a person to break the law or to take part in mob justice is to “trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the charter of his own, and his children’s liberty.” Americans should therefore teach “reverence for the laws” in homes and schools throughout the land – not because law is our ultimate political good, but because the law preserves American liberty and equality.

An 1858 speech in Chicago is also instructive. In it, Lincoln argued that a person who has no ancestral connection to the American Revolution, regardless of their race or place of origin, “when they look through that old Declaration of Independence,” finds the words “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” and then they realize that they “have a right to claim” America and the American heritage “as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration, and so they are.” He continued, “This is the electric cord in that Declaration that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world.”

More to the point, in his 1852 eulogy on Henry Clay, Lincoln said of Clay, “He loved his country partly because it was his own country, but mostly because it was a free country.” It is not just that this America is my homeland, but in this land, we are free, and we always mean to be.

The heart of the American patriot is warmed at the hearth of the American constitutional order, one that enshrines human liberty and equality. For over a century, Americans have pledged allegiance not to a land, not an ethnicity, and most certainly not to any politician or president. We Americans have pledged allegiance to a flag, and to the republic for which it stands. May it long be said of us.

Bill Reddinger is Associate Professor of Government in the College of Arts & Sciences at Regent University, where he teaches courses in political philosophy and American politics. His book, Political Thinkers for Our Time, is forthcoming from NIU Press.