A Biblical View of Taxation

Editor's Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Regent University, its faculty, administration, or affiliates.

This year’s election has been unique in many ways, and there are several open questions. Regardless, we know one thing for certain: Tax policy will be an issue; it always is.

As Christians, we should view political issues through a biblical lens. Sometimes, we see clear admonitions. Other times, we see principles and general approaches, but the details are less specific. Tax policy is like that, which makes it difficult to claim one’s view is based on biblical principles. That also makes it easy to project our views onto some cherry-picked verses, which makes the whole conversation a muddle. But we know God is not the author of confusion, so we should be able to find some clarity.

First, some tax basics: There are two types of economic activity that can be taxed—flows and pools. A flow is when money moves from one to another, such as purchases (sales tax) or pay (income tax). A pool is an asset, and its taxes include real estate and personal property tax.

The other part of the tax system is who pays the tax, and there are three general approaches: a progressive tax, a proportional tax, and a regressive tax. A progressive tax taxes the person at a higher rate based on higher value or income. The federal income tax is an example; the more one earns, the higher percentage one pays. The Tax Foundation reports that the federal income tax is progressive with the top 10% of income earners paying 73% of the total income taxes paid in 2020.[1]

With a proportional tax, commonly called a flat tax, everyone pays the same percentage. State sales taxes tend to be proportional. Finally, there’s the regressive tax—the poorer one is, the more they pay. This sounds unfair and would never be used. One would be challenged to find a tax structured this way, but the reality is that some taxes result in regressivity. An example is state cigarette taxes; lower-income people tend to smoke more than higher-income people, thus making cigarette taxes, effectively, regressive.

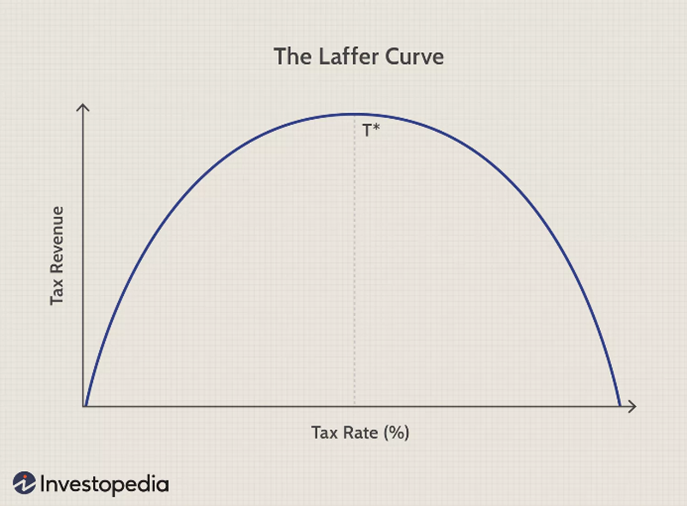

The only other thing to consider is the Laffer Curve—a relationship between tax rates and tax revenues, which explains that higher rates do not mean more revenue. There’s an optimal tax rate, and any other rate, lower or higher, results in collecting less tax revenue, since taxpayers find ways to avoid paying. It’s basic-cost benefit. If rates are low, pay the taxes, but if rates are high, it’s worth finding ways around paying them.

That’s it. The code need not be very long and the forms not very complex. In the early years of the federal income tax (pre-1920), the 1040 was four pages long.

So, while Scripture does not give us a prescription, especially for a modern secular government, God’s Word does give us some principles.

What should be taxed? In Scripture, we see that income was the primary focus of taxation. While the tithe is not a tax in the sense we mean, it was a requirement and was 10% of a person’s production (Deut. 14). Long before this, Abraham offered Melchizedek 10% of the plunder after rescuing Lot (Gen. 14), and Joseph taxed the Egyptians for 20% of their production during the seven good years (Gen. 41).

How should the tax be structured? As described above, all these taxes were proportional. And that’s consistent with commands to not favor the wealthy or the poor. However, there is room for some progressiveness in the tax structure. Some aspects of the sacrifice system allowed for higher- and lower-valued animals (Lev. 5). Either way, simplicity and understandability were paramount; God’s tax code is less than 50 words.

What should the rate be, and what is the optimal tax rate in the Laffer Curve? This is a challenging question, and we only have one guide on this. My professor Walter Williams used to say if 10% is good enough for the Baptist church, it’s good enough for the government, obviously referencing tithing. But, with all due respect to Professor Williams, there’s another example that may be more applicable: Joseph in Egypt. Joseph knew Egypt was facing a severe economic crisis and was incentivized to maximize the grain collected during the seven fat years. He set a 20% flat tax rate on agricultural production. If a higher rate would have collected more grain on net, I’m sure—although we’re not told—he would have used it. But Joseph, perhaps showing early knowledge of the Laffer curve, possibly realized that a higher and a lower rate would have collected less grain.

Should the government maximize its net tax collections? That’s a different question, but if 20% is an optimal rate, then anything above 20% is counterproductive. It’s more than interesting that the average revenue collected by the federal income tax has been about 18%, no matter the rate. (See the graph below.) In effect, despite thousands of pages of tax code and dozens of changes over the years, the federal income tax has resulted in an outcome that looks very much like a 20% flat tax.

What ‘s applicable from all of this to modern tax policy? First, we’re to pay our taxes (Romans 13). Paul wrote that letter when Rome ruled, so arguments about government being un-Godly are not valid reasons to withhold our taxes. Second, the tax code, to be biblically consistent, should be simple, understandable, and show no favoritism. It can be mildly progressive, but, in the main, it should have a proportional (flat) structure. It seems, both from Joseph’s actions in Egypt and our own history, anything much over 20% is useless and a waste of resources.

But there’s certainly room for discussion.

[1] See the Tax Foundations website for the full report: https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/federal/summary-latest-federal-income-tax-data-2023-update/